:Dr. Akmal Hussain, an economist, author and social activist and Engineer Hassan Jaffar Zaidi, CEO, Power Planners International, an energy consultancy firm, deliberated on the impact of structural complexity, institutional bottlenecks, governance and organizational management related to the power sector in a CPPG policy dialogue titled “Institutional Bottlenecks and Management Issues in the Energy Sector” on July 25, 2013.

Dr. Akmal Hussain began by stating that an energy crisis emerging in a country with a 100,000 MW hydropower potential was testament to the management failure of past governments and institutions. Having advised various governments and prime ministers since 1988, he pin pointed successive governments’ focus on short-term solutions while ignoring long term problems as the basis of the current energy crisis. Quoting from his 1988 book, he stated that academics had highlighted the coming crises as early as 1988 but a policy with long-term implications was never considered because each government was only interested in short term results. However, governments could not be singled out as it was the responsibility of the institutional structure to ensure that governments worked on strategies for a permanent solution to the crises. He gave the example of mature states where the institutional structure obliged the government of the day to undertake policies for the long term while addressing immediate concerns such that governments did not merely become fire fighting units.

Hussain then elaborated on three aspects of the origin of the crises, which had unleashed mass scale human misery through increased poverty and unemployment, a serious balance of payment crises and pulling down of economic growth by 3%. One, the failure to invest in hydroelectric power in the decade of 80s and 90s had led to a shift in the energy mix from 60% hydro in the 1960s to 30% in 2009-10 leading to the use of high cost energy sources, and costs rose further with the increase in oil prices. He put the responsibility for this on the lack of long-term planning and research as the gestation period for hydroelectric dams was 8-10 years, and a failure to invest in them led to short term solution of using furnace oil and gas thermal power plants to produce electricity. Two, economic growth in the Musharraf era was not supported by growth in the installed power capacity. Estimates showed that 1% GDP growth should accompany at least 1.5% yearly growth in installed power capacity. But from 2002-07 when average GDP growth rate was 7%, the average annual installed power capacity growth rate was just 2.2% leading to growth un-sustainability. Three, the failure to invest in the maintenance and up-gradation of existing power plants led to available production capacity being half of the installed capacity. Because there was no obvious shortage of electricity during the Musharraf period, the public sector did not focus on investing in the power sector while the IPPs did not upgrade their plants owing to a lack of investment security either because of an uncertain government policy or an uncertain political future.

“…institutional restructuring and governance were pre-requisites for a successful implementation of policy.”

The above stated issues existed when the PPP government came into power in 2008, however the scale of the problem was much greater than its management capacity. The cost of electricity production was almost Rs. 14 per unit and if tariffs were fixed equal to cost, electricity prices would have risen by 50% possibly leading to riots. Thus the government only did firefighting and agreed to subsidize power distribution companies by Rs. 5 per unit keeping the consumer cost to Rs. 9 per unit. But the cost of subsidy (Rs. 5 per unit) was too high and consequently the government failed to pay the distribution companies who in turn couldn’t pay power production companies who couldn’t pay the oil companies leading to an oil shortage. This came to be termed “Circular Debt” with the consequence that power couldn’t be produced even from the existing installed capacity.

“… rather than following the NPP, the 1994 Energy Policy instead followed the neo-liberal dictates of global capitalism.”

Hussain then articulated recommendations for the short and long term. He stated three recommendations for the long term: first, investing in hydroelectric power production to change the production mix for cheaper electricity; second, investing in more efficient transmission technologies; and three, restructuring the entire institutional framework of the power sector for a more efficient transmission and load management strategy and for stopping theft. Putting greater stress on the need for immediate relief, he made five short term suggestions. Firstly, mobilize finances to get rid of the Circular Debt estimated at Rs. 870B (government figures put it at Rs. 500B) to produce at least the level of available capacity, which can add 5,000 MW and would suffice the existing suppressed demand levels of about 4,978 MW. Secondly, improve available capacity to installed capacity by first analyzing and identifying the supply, maintenance and repair constraints of power production companies to reach installed capacity and then where possible conduct interventions by supplying funds, material or technical expertise to ensure production up to installed capacity at a reasonable efficiency level. Thirdly, stop theft by changing the organizational and monitoring system of distribution companies and by improving transmission technology to decrease losses. Out of the 28-30% attributed to line losses, only 7% was due to transmission technology while the rest 23% was theft. The DISCOs lacked the basic human resource capacity to run efficiently while existing rules and enforcement mechanisms allowed massive theft as even an XEN could sell uninterrupted electricity to large buyers while shifting the load burden to other consumers and pocketing the money. Fourthly, conduct better load management by efficiently managing shortage of electricity in a just and equitable manner ensuring minimum human suffering through scheduled load shedding. The DISCOs didn’t have a metering system or capacity to calculate electricity flow on an hourly basis and could only conduct a monthly estimate. Thus as they tried to reorganize the distribution of electricity to manage hourly fluctuations in the supply system and to further squeeze more electricity out of the already stretched system, it led to tripping – unscheduled load shedding. Fifthly, install smart meters at the consumer level to encourage energy conservation as these meters can calculate consumption according to different times of the day and thus allow variable pricing at peak versus normal hours. Additionally these can also ensure just and equitable mechanism for subsidizing low-end consumers.

“…it was the responsibility of the institutional structure to ensure that governments worked on strategies for a permanent solution to the crises.”

In conclusion, he agreed with the strategy adopted by the new PML-N government to eliminate more than half of the circular debt in a week raising production by about 5,000 MW and also with the government’s stated goals: 1. Build the power generation capacity that can meet the country’s needs; 2. Ensure generation of inexpensive and affordable electricity for domestic, commercial and industrial use; 3. Minimize pilferage and adulteration in fuel supply; 4. Promote world class efficiency in power generation; 5. Create a cutting edge transmission network; 6. Align ministries in the energy sector and improve governance. However, he argued that the challenge for the current government was to develop an effective implementation mechanism for achieving these policy goals as theft had become institutionalized creating a secondary market for energy. He articulated that institutional restructuring and governance were pre-requisites for a successful implementation of policy. Defining an institution as a set of rules embodying incentives and disincentives to shape the behavior of individuals and organizations, he argued for an institutional restructure of the power sector involving rules, regulations, systems and contracts to ensure efficiency. Additionally, a governance framework with just the right incentives, transparent, equitable and enforceable rules, and efficient mechanisms was needed to attract foreign investment. Suggesting that $3 trillion crossed international borders every 24 hours looking for good investments, he argued that with the right governance framework, Pakistan could attract private investment in cutting edge technology to improve transmission and distribution systems and in coal-based plants, run of the river plants and hydropower dams.

Table 1: Electricity Supply and Demand

Engineer Hassan Jaffar Zaidi continued the focus on the institutional framework of energy sector by elaborating on the historical evolution of its current structure. He stated that till the mid 90s, Pakistan was on track planning for reserves and had a strong transmission system of 500 KV lines compared to that of North America, in addition to the 220KV, 132KV and 11KV networks. The power sector was managed by WAPDA headed by a Chairman and three Members: Power, Water and Finance. There were 12 Electricity Boards each headed by a Chief Engineer. In 1994, a National Power Plan (NPP) based on a least cost generation plan was developed for the 1995-2018 period which envisioned an energy mix of 42% hydro including Ghazi Barotha, Kalabagh, Basha, Kohala and Tarbela extension, and 32% thermal located mostly at sea coast using combined cycle technologies based on coal and indigenous gas. However, the end of the Cold War with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 ushered a new era of neoliberal global economic order with market economy and privatization as its key instruments. Thus rather than following the NPP, the 1994 Energy Policy instead followed the neo-liberal dictates of global capitalism instituting the following changes: one, no power plant was to be funded in the public sector; two, government organizations were to be privatized and a Privatization Commission was formed for this purpose; three, the persistent policy of generation and transmission planning based on least cost & other parameters was abandoned, and instead IPPs were invited to install power plants anywhere suited to them irrespective of consideration of fuel, technology or logistics; and lastly WAPDA was asked to unbundle into 14 companies with the objective of privatization. The result was that while Pakistan had a small reserve in 2000, the short fall increased overtime and by 2012 load shedding in terms of energy increased to 27.5% of the national demand.

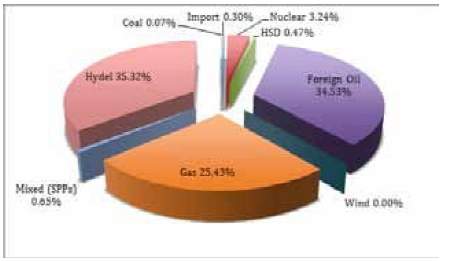

Figure 1: Fuel Wise Power Generation 2010-11

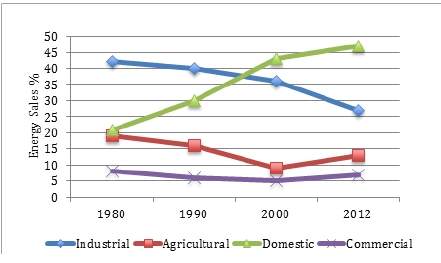

In discussing the evolution of energy mix, Zaidi argued that roots of the energy crises lay in our commitment to global capitalism as the same policies were followed irrespective of who was in power in Pakistan. Thus investment in bigger hydro power plants stopped as the public sector took a back seat while the private sector only came up with smaller projects which had comparatively higher generation costs and lower efficiency. HUBCO with 1,200 MW was the biggest plant set up while all others ranged from 200-400 MW. Over time, the hydel-thermal energy mix changed from 69:31 (1960), 45:55 (1990) to 35:65 (2010) and 30:70 (2013) while distribution of power generation changed to 48% private and 52% public. Additionally within thermal, the gas component in 2011 comprised of 25.43% while furnace oil was 34.53% as the power sector did not get the needed gas owing to CNG usage in transport. Thus as the furnace oil component increased, so did fuel costs which led to higher electricity rates. The problem was further compounded because the productive aspect within the consumption pattern decreased with the increase in domestic component at the expense of industrial consumption.

“…there was a severe lack of ownership and initiative in the sector as lack of tenure security led to indecisiveness at all levels affecting institutional stability.”

Zaidi then analyzed the restructuring of WAPDA which was unbundled into 14 companies in 1998 with the objective of privatization. The original Power wing was made the National Transmission and Despatch Company (NTDC) and given the 500KV and 220KV networks, while its Area Boards became ten independent distribution companies (DISCOs) each headed by a chief executive with a team of 7-8 general managers and chief engineers responsible for the 132KV and 11KV networks. Additionally three generation companies (GENCOs) were also created such that WAPDA was reduced to the handling of dams and water related energy issues only. Commenting on the new structure, he argued that to hide their lack of expertise, mismanagement and corruption a new term ‘administrative losses’ was coined. He stated that distribution and transmission losses could not technically be more than 10-11% and thus the rest had to be theft, mismanagement and corruption which was highest in Northern Sindh (45%) followed by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (37.4%), Southern Sindh (32.4%) and FATA (21.6%).

Figure 2: Electricity Consumption Pattern

He suggested that the evolved institutional structure was at the core of power crises today specifying four areas. First, the biggest flaw was that the core technical departments like planning, design, protection and communication stayed back with NTDC and were not developed in the DISCOs. The DISCOs were also given the 132KV network which had always been planned, designed and managed by the department which was kept with NTDC leaving the DISCOs with no capacity to conduct simulation on the network they controlled. Additionally, without agreed governance rules, the DISCOs and NTDC were unclear about the situation in the other’s network leading to mismanagement. Second, while WAPDA had a simple structure whereby decision making authority and accountability lay with four people, now each of the fourteen companies had its own management leading to a top heavy management structure. For example, the Lahore Area Electricity Board earlier run by a Chief Engineer had now become LESCO with its own Chief Executive Officer (CEO), 4-5 General Managers, 8-10 Chief Engineers and a 15-16 member Board of Directors. Third, the set of rules that had been followed earlier by one entity were not properly set or managed through the rules of interaction for fourteen independent entities. For example, all power generation from IPPs, WAPDA, GENCOs, Small Power Plants (SPP)/Captive Power Plants (CPP) still went to one entity creating a single buyer market and a power pool called the CPPA, which distributed it to the DISCOs and KESC. Fourth, although all fourteen were private limited companies on paper, in actuality they were owned by the government, controlled by PEPCO and run by the Ministry of Water and Power through adhocism and stopgap arrangements with complete disregard for managerial aspects leading to poor governance of the power sector. For example, PEPCO sometimes stood dissolved with extra charge given to Managing Director (MD) NTDC. For the last four years, NTDC did not have a full time MD while Joint Secretary Water & Power held the additional charge of MD NTDC and PEPCO during the last two years. The Board of Directors (BoD) was constituted and dissolved in rapid intervals and it had no BoD for the last two months. DISCOs presented an even more anarchical situation as CEO LESCO had become a game of musical chairs since the last two years. Members of BoDs of all companies were political appointees with no or little merit for the position. Thus, there was a severe lack of ownership and initiative in the sector as lack of tenure security led to indecisiveness at all levels affecting institutional stability. The Rental Power scandal while keeping the politicians unharmed had led to the prosecution of some power sector employees involved in paper work further harming the environment as many engineers now refused to touch new projects instead using delay tactics to avoid taking responsibility.

“… provincialize DISCOs to resolve the theft problem by ensuring that provinces were responsible for bill collection under their law & order mandate.”

After providing an overview of the past and present, Zaidi presented options for the future by explaining the National Power System Extension Plan (NPSEP) prepared in 2011 by the NTDC updating the 1993 plan of which only Ghazi Barotha in hydro and Ucch Power Plant in thermal were implemented. Zaidi had participated in the preparation of both plans and stated that the 2011-30 plan was based on indigenous components with present situation as the base year. It envisioned a change in the energy mix to increase the hydro component from the current 28% to 37%, Thermal Coal from 1% to 34% while decreasing Thermal Gas from 31% to 11% and Thermal Oil from 37% to 6%. He argued that if this plan was implemented, Pakistan could cross the peak load by 2018 though it required huge investments of about $400B by 2030. But the government had yet to take any action on the plan. He suggested that underground coal was not a unique situation as it was being used by other countries primarily through mining. We just needed to decide if gasification or mining was the way forward. Nuclear energy initiative was being conducted through the collaboration of China and Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission. In renewable energy, wind power had been neglected because of a lack of knowledge and capacity owing to the lack of culture of taking risks on new things.

He further explored the bottlenecks in Public Private Partnership that restrict investment suggesting that while investors were coming in a big way, the institutional hurdles didn’t facilitate them. The process of starting a new project included PC1 approval from the Planning Commission and ECNEC, procurement of land for sub-station, right of way for transmission line, arranging of funds from own sources or international donors, and an initiation of the process of transmission and interconnection schemes before actual construction could start. While the average time of 3-4 years given to private producers for connecting their power plant with the grid operator’s transmission line was fine for thermal or hydro projects, it did not work out for solar and wind IPPs as their plant could be ready within 12-18 months. Additionally, the CPPA was not ready to start negotiation on energy purchase agreements till after the grid was available. As the IPPs required complete paper work to arrange funding which took 3-4 years owing to transmission connection, investment in renewable energy was locked up. Thus the wind corridor with the potential of 20,000 MW was stalled while the solar potential in Cholistan with proposed 500 MW or 1000 MW IPP plants was restricted as the current 66 KV line could only carry 30 MW while a 220 KV grid required 3-5 years to complete. Further, the small IPPs of less than 50 MW were knocking on various doors without success as the NTDC or CPPA’s doors were closed to less than 50 MW plants according to the Energy Policy while the DISCOs argued that they did not have the capacity to write an EPA.

“…the National Power System Extension Plan which had been developed recently through thorough study and simulations should be followed without delay.”

The last part of Zaidi’s presentation concentrated on policy recommendations. He emphatically argued for formulating an integrated and coordinated energy policy whereby initial planning was done centrally to ensure proper coordination between the various institutions while implementation was done in a decentralized way. Additionally, emphasis had to be on indigenous resources and the public sector needed to focus on mega projects, otherwise the current crisis would be curtailed in the short run only to appear again in the future. He specifically critiqued the direction taken by Chief Minister Punjab who had asked WAPDA to suggest five locations for 1,000 MW coal based plants in Punjab, convert existing oil based plants to coal and establish 50 MW coal based plants at Lahore, Faisalabad and other cities, all based on imported coal. He pointed out three issues with this plan; one, the needed infrastructure was not available due to a lack of special bogies for transportation of coal, railway tracks and the capacity of Karachi port to import so much coal; two, coal was increasingly becoming expensive in the world market and thus a long term perspective was needed to ensure that another CNG scenario was not repeated; three, there were environmental hazards of establishing coal based plants near populated areas and instead, a better option would be to put up imported coal plants on the coast and have transmission lines bring electricity to the needed areas.

Delving into the changed scenario post 18th amendment which gave provinces the right to setup energy plants, he stated that provinces still did not or have limited capacity as they could not ensure sovereign guarantee to international lenders. Giving the example of India where 50-60% power was handled by provinces through State Power Boards linked together through a National Grid Company, he argued that provinces needed to develop their own financial and institutional capacity. This included having own CPPA, Power Purchase Agency and a Power Development Board to manage the electricity produced and distributed in the province while inter-state power purchase was handled by the Council of Common Interest. This further required abolishing PEPCO and provincializing DISCOs to resolve the theft problem by ensuring that provinces were responsible for bill collection under their law & order mandate. He further argued that the rules of free market economy should be applied to DISCOs, who should directly buy power from IPPs while only paying NTDC for transmission of power.

Lastly, Zaidi tied the success of energy policy to management of internal and external politics suggesting its importance by providing examples of Kalabagh dam, the Diamer-Bhasha project whose foundation stone had been laid four times in the last 10 years without any progress, and the cancelled 900 MW Chashma nuclear plant agreement between Z. A. Bhutto and France. He further presented four possible projects with international implications: one, the Iran Pakistan Gas Pipeline whose future was uncertain; two, import of 1,000 MW power from Iran whose detailed feasibility study including the nut and bolt of transmission line was ready along with a commitment from Iran to accept barter trade of gas against wheat and rice; three, a 2,000 MW import of power from Central Asia – South Asia (CASA) intertie was lingering for years; four, a plan assessed in the 2006-7 NESPAK study to interconnect the grids of Economic Cooperation Countries (ECO) could free all 10 countries from international hegemony even without new generation as their peak times were different along with varied generation mechanisms but no progress had been made on this front. In conclusion, he made his overall recommendations: one, the National Power System Extension Plan (NPSEP) which had been developed recently through thorough study and simulations should be followed without delay; two, concentration should be paid to indigenous coal and gas while imported oil use for any future power plant should be declared a criminal offense; three, financial mismanagement should be addressed and structural reforms of the power sector should be carried out on an urgent basis; four, NTDC and DISCOs should enhance their capacity to improve partnership with IPPs; five, public and private sectors should pool all renewable and indigenous resources on hydel, coal, solar and wastes (urban, rural, industrial and agricultural); six, government should invite investment on big thermal plant sites identified in NPSEP; seven, initiate regional cooperation to facilitate import of power from Iran, Central Asia and India without buckling under international pressure. He closed with a rhetorical question giving the example of Ethiopia which was constructing a 5,000 MW hydropower project costing $4.8B with little help from China but mainly through funds generated internally from her own people rather than international loans. He asked if Ethiopia, a poor country could do it, why couldn’t we?

“…NTDC or CPPA’s doors were closed to less than 50 MW plants according to the Energy Policy while the DISCOs argued that they did not have the capacity to write an EPA.”

Citations