:Dr. Nosheen Ali, visiting scholar at the Center for South Asia Studies, University of California Berkeley was invited to deliver a talk on “From Protests to Poetry: Contesting Sectarianism in Northern Pakistan” on December 2, 2010.

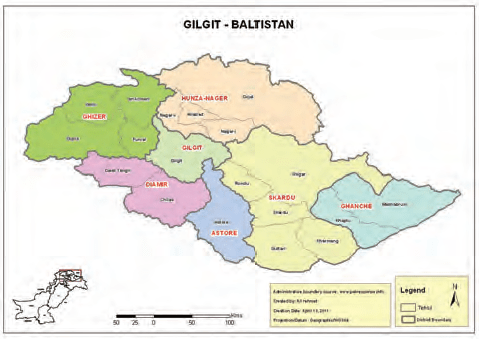

Nosheen Ali opened her remarks by explaining that Gilgit Baltistan (GB) was an area with pronounced sectarian conflict and violence. Over time, sectarianism had seeped into the social structure of the region but its comprehension required an understanding of state building and governance in Gilgit Baltistan. Showing an older map of Pakistan, she pointed out that Northern Areas (As Gilgit Baltistan was earlier known) was part of the larger internationally disputed territory of Kashmir claimed by both Pakistan and India. It was under Pakistan’s administration but Pakistan’s policy regarding the region had been inconsistent and irresponsible.

She argued that the sectarianism narratives in Pakistan were primarily from the political science and international relations perspective highlighting only few factors. Additionally, primordialist arguments stating that Shia-Sunni differences have existed since 1400 years, have caused conflict and will continue to in the future were usually given. This argument that difference inevitably leads to conflict was flawed as social history showed otherwise. Theology obviously fostered a sense of difference, however, modern political structures needed to be analyzed to understand the rise of sectarianism. Another narrative on sectarianism attributed it to variables like illiteracy, proliferation of Madrassas etc. Although these factors were relevant, still they were not enough for us to understand the regional and historical context in which sectarianism emerged. Lastly, though international factors like the Afghan War were instrumental in increasing sectarian violence, still the linkages between the two needed to be traced. The question one needed to ask was how the Afghan War translated into conflict in Northern Areas. This linkage and trajectory was not properly traced out in contemporary analysis of sectarianism in Pakistan.

To analyze public policy, it was important to have a comprehensive understanding of the State. A narrow perception of the State was mainly understood through the parliament, the judiciary, the police and so forth while not recognizing school textbooks, cultural policies on Pakistan Television as also part and parcel of the State. She argued that examining the ideological apparatus of the State was essential and realizing that education was a major part of this apparatus very important. There was a need to look at more subtle ways in which State policy perpetuated itself and one of the ways was through public school textbooks.

Ali began her analysis by providing the regional context of the issue. Gilgit Baltistan was the only Shia majority political unit in Pakistan. Along with the fact that it was a disputed Kashmiri territory, being religiously different and territorially unsettled produced a sectarianism based on a very different cause and consequence structure. While usually sect was analyzed in terms of laws, madrassas and political structures, it was important to understand sectarianism at an emotional and everyday social level by moving the analysis away from political structures to daily social life.

Historically, sect was never a marker of identity in Gilgit Baltistan. It was the tribe or “qaum” that stood out. The regional or tribal identity was the primary identity of the people and intersect marriages were common. Religion was not taught in schools so the question of, what was taught leading to whose Islam was right never arose, and so conflict was avoided. Gilgit Baltistan had a history of managed pluralism where interregional marriages were encouraged; women and marriage were both used as tools of political resolution and it was considered necessary to accommodate different interpretations of religion for the security of the political and moral order.

“…argument that difference inevitably leads to conflict was flawed as social history showed otherwise.”

Ali then proceeded to describe some of the key events which were critical in understanding how the situation in the region changed. In the 1970’s a secular nationalist movement emerged in GB that struggled to achieve political and democratic rights. The “Jail-breaking incident” that occurred during this time was of prime importance. It involved army highhandedness provoking the masses (thousands of protestors) to come out on the streets. The protestors were jailed but more protestors came out demanding their release. The movement became so powerful that the protestors eventually broke into the jails and freed the jailed protestors. An important occurrence during these protests was the refusal of Gilgit Scouts, an army unit established by the British in 1913 to fire on the protesting crowd as ordered by the then district officer. In reaction, the Pakistani State broke up the Gilgit Scouts in 1975 and replaced them with frontier troops from Peshawar. She explained that regional troops usually managed the area better and thus this government decision mainly served as a means of dividing people as the presence of troops from Peshawar was still greatly resented in Gilgit Baltistan. Additionally, to counter the secular nationalist rights based movement, the State through intelligence agencies started funding religious leaders and clergy of both sects. This State policy sowed the seeds of sectarianism in one of the most peaceful intra-Muslim areas. The 1988 violence in which 12 villages were burnt, 800 Shias killed, animals were slaughtered and trees were cut down was one of the worst incidents of sectarian violence in Pakistan, but had not been properly documented. Still everyone in GB remembered it and it was part of the psyche of the region.

“Religion was not taught in schools so the question of, what was taught leading to whose Islam was right never arose, and so conflict was avoided”

A major and most recent sectarian conflict that the region had seen was the issue of textbooks. Both the 1988 violence as well as the current textbook conflict occurred during the military regimes while policies most favorable for the region were implemented during civilian times. It was both under civilian governments that the 1974 feudal system ended in the region and the Gilgit Baltistan Ordinance was changed last year. Explaining the textbook conflict, she said that it was a movement that went on for over five years in Gilgit Baltistan, severely aggravated the sectarian conflict and shaped the recent history of the region. Generally, it was recognized that extremist mentality, both anti-Hindu and anti-Christian content was present in our textbooks. But we must also recognize that textbooks were sectarian (anti-Shia) which was a major issue in Shia majority GB. A study conducted in Gilgit Baltistan showed that that curriculum of English, Urdu, History, and Drawing from Class 1 to FSc had a sectarian and ideological bent. This led to a peaceful movement by the Shia community to replace these textbooks, which lasted five years. They sent delegation after delegation requesting to undo curriculum reflective of only one dimension of Islam and instead demanded that only consensus-based concepts be included to ensure that the curriculum was reflective of all sects. She thus called it a secular Shia movement.

“…to counter the secular nationalist rights based movement, the State through intelligence agencies started funding religious leaders and clergy of both sects.”

This progressive demand put forward by the people, however, was seen and portrayed by the Pakistani media and State as a Shia movement. People got together to form legal committees and challenged acts of discrimination and sectarianism. A peaceful and progressive call for changing sectarian curriculum was given a heavy-handed response from the army and rangers, resulting in a rising death toll, curfew for 11 months and a complete shortage of staple items. It showed that people in Pakistan were capable of bringing about change but a lack of aptitude by the government in handling the situation completely defeated the purpose and created further conflict. Due to a repressive State policy, the movement was transformed from being against the State into a Shia versus Sunni movement (conflict). Assassination of the popular progressive Shia leader Agha Ziauddin further exacerbated the situation and was one of the key events that led to worsening of sectarian violence in Gilgit Baltistan. She challenged the many analyses terming them incorrect that claimed that Pakistanis had never raised their voice against sectarianism, giving an example of GB where people demonstrated their resistance at a social level. Thus, one needed to acknowledge the resistance of ordinary people to sectarianism. However, it was interesting to note that the textbook controversy and other incidents in GB rather than being well reported were minimally reported leading most of Pakistani public to believe that all was well in Gilgit Baltistan.

Highlighting the role of poetry to counter sectarianism, Ali explained that when the situation in GB got out of control with extreme daily widespread violence, poets of the region were provoked and decided to employ poetry as a means of resolving issues and promoting peace. Thus moving beyond protests, poetic method was used for social resistance and change. Poetry had historically been the source of Islam in the region and was a form of religious and devotional knowledge for the people increasingly in terms of progressive values. Government officials and the poets came together in the Halqa Arbab-e-Zauq to resolve the sectarian problem through poetry. They organized a conference and a Natiya Mushaera (poetry gathering in praise of the prophet) and invited maulvis (clergy) of both sects to attend. It created a perception and belief that not attending the Natiya Mushaera was an insult to the Prophet implying that the religious leaders could not turn down the invitation. The Natiya Mushaera proved to be an effective strategy in bringing together religious leaders of both sects, and thus provided a space and opportunity to break the ice. The invited religious scholars discussed and propagated concepts of unity among Muslims.

In concluding her talk, Ali stated that in the context of sectarian violence, peaceful poetry constantly served to remind people of common values, humanity and a progressive vision of ethics and politics. During interviews conducted of the poets, they had said that their purpose was to promote harmony, humanism, and a peaceful vision of Muslim ethics and politics. She emphasized that it was important to recognize poetry as a means of social change and movement. In Gilgit Baltistan, it had been used to challenge the sectarian policy perpetuated by the Pakistani State.

“…poets of the region were provoked and decided to employ poetry as a means of resolving issues and promoting peace.”

Dr. Aslam Syed, Visiting Professor University of Berlin, shared his thoughts as a discussant pointing out that religious sectarianism and disputes also needed to be assessed based on economic and socio-political reasons. He highlighted three aspects; one, the building of Karakoram Highway while contributing immensely to the development of the region had also changed the socio-economic outlook of the people; two, the citizenry had been asking for their rights as full-fledged citizens of the country and three, a reflection of neglect of the people of the region and of State policy implementation to keep the area calm and quiet. In response, Ali emphasized that although development was important, still it was not a replacement for granting political rights to the people. The situation in GB had improved since granting of the autonomous status. The political systems would be further strengthened with time. Additionally, she differed on the role of the State arguing that State policy had created the conflict through promotion of sectarian mentality rather than to keep the area calm. This had led to deep sectarian resentment and sectarian bias in various themes because people had become suspicious of the other, always protecting their own territory. She pointed that the text books issue had still not been resolved. The main issue was that Gilgit Baltistan did not have its own textbook board as it lacked proper constitutional rights. It had been teaching the Punjab Text Book Board books and rather than a radical change in curriculum had opted to replace these with the National Book Foundation books which were considered better. Two books had been replaced but the struggle was ongoing. She argued for a separate Text Book Board for GB which could produce non-sectarian books as a model for the rest of Pakistan.

In response to a question regarding religion and poetry, she stated that there was no divide between secular and religious poetry as human values and knowledge of the divine were both poetic themes, and were very much integrated for the people of Gilgit Baltistan. Further, elaborating poetry’s role in politics she mentioned that it bridged the gap between Shia-Sunni communities by bringing both sects together during the textbook conflict. Additionally, incidents particular to Gilgit Baltistan history such as the fact that Gilgit Baltistan was the only region that fought a war to become part of Pakistan, were also discussed through poetry.

Explaining the linkage of sectarian violence in Gilgit to the Afghan War, Ali posited a direct and clear link. The Afghan War created madrassas and hate ideology with millions of dollars. A big part of this ideology and books were vehemently anti-Shia. Additionally 1988 violence was different from the local sectarian violence. The theory was that it was perpetrated to teach a lesson to the people of Gilgit Baltistan who had earlier stopped the Afghan War veterans and lashkaries (fighters) on their way to Kashmir just like few communities who had resisted the current Taliban. This violence was part of the organized program which tried cultural annihilation by forcing the Shia to pray behind the Sunni imam or re-marriage of marriages earlier consummated under Shia law.

“The main issue was that Gilgit Baltistan did not have its own textbook board as it lacked proper constitutional rights”

Answering a question regarding the use of technology in Gilgit Baltistan, she mentioned that mobile phones were made available in GB only in 2006 and were not allowed before. However, mobile phones were still being tapped and civilians were deeply hurt by the mistrust of the State towards them. While accepting that the role of technology for progress could not be denied, she argued that a structure guaranteeing rights to the people was essential for development, and there was no alternate to rights and respect.

“…a structure guaranteeing rights to the people was essential for development, and there was no alternate to rights and respect.”

Citations