The technical session was chaired by Dr. Naushin Mahmood, president of PAP. The session was moderated by Dr. Aliya H. Khan Chairperson Department of Economics Quaid-i-Azam University. Dr. Saeed Shafqat presented his paper on Demography, Security and Governance: Emerging Trends and Implications for Pakistan, Mr. Minhaj ul Haque on Tapping Potential in Youth: Policy Challenges and Prospects, Ms. Tayyaba Batool & Dr. Aliya H. Khan on Determinants of Female Labor Force Participation: A Case Study of District Khushab, Mr. Zafar Mueen Nasir on Human Resource Development and Employment, Mr. Ali Raza Khan on Transforming Youth from Victims to Social Entrepreneurs and Ms. Grace Clark on Older Persons in Pakistan: Budget Drain or Productive Asset. Dr. G. M. Arif Dean Faculty of Development Studies, PIDE acted as the discussant for the session

Haque describing the need for youth based analysis argued that managing the largest youth cohort (69% of the population under 29 years of age) in our history presented a tremendous challenge especially when no youth policy has been in affect for the last 8 years. Consequently, no informed debate on relevant programming and policy formation has taken place.

Haque began by presenting women as the hidden population of Pakistani society due to the great gender disparity in education and work (put graph) and described it as our great economic productivity loss. Poverty affected women disproportionately assessed by the fact that the mean educational achievement of the male child of the poorest quadrille was 4.2 years of education, while for the girls it stood at 0.6 years. Examining the factors behind high drop out rates, he observed that parental attitudes adversely affected girl’s education and mobility. He observed pay ability and lack of interest ranked highest in male drop out rates at 39% and 33%. In case of girls, it was parent’s disapproval at 24% that ranked highest; followed by pay ability, accessibility and family responsibilities at 23%, 22% and 21% respectively. The greatest disparity though lay in mobility with only 13% girls being able to go the health clinic alone compared to 95% boys. Unaccompanied female mobility stood at 26%, 39% and 57% for visiting a shop, school or a neighbor compared to 99%, 99% and 94% for males.

Phrasing it as change as well as dexterity of Pakistani youth, Haque claimed that 50% of Pakistani boys in the age of 15-19 were already working while an additional 46% were willing to work if provided employment. For girls, the same numbers stood at 25% and 58% but a more interesting aspect was the generational shift with 83% girls between the ages of 15-19 wanting to work compared to 78% between the age of 20-24.

: Transition to Adulthood

Tayyaba Batool further nuanced the determinants of Female Labor Force Participation (FLFP) in terms of spatial aspects. Batool presented a case study of Khushab district, interviewing 205 females from rural and urban sections of the district. She found that the FLFP of the district at 33.7% was much higher compared to 19% female national average.

Her multivariate analysis affecting female labor participation showed no significance for variables including number of children and household members, husband education and region (urban/rural) while female education, skills, marital status and household income mattered most. The most interesting aspect of her findings was FLFP association with education as illiterate women, primary educated, matriculate, college and post-graduate women labor participation stood at 23.3%, 10.5%, 25.5%, 66.7% and 80% respectively. Thus indicating that labor participation decreased with education till a woman completed her matriculation. This phenomenon requires further analysis to understand the complete picture. Technical education stood out as the most significant educative factor for FLFP as 90.5% of women with technical education participated in the labor force compared to 27.2% with no technical education. Further generalized to skills, Batool’s results showed that 40.2% of skilled women participated compared to the 24.1% unskilled.

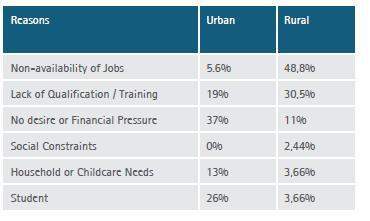

Haque had earlier presented youth’s distribution of paid work showing agriculture and livestock dominating at 39% for females and 30% for males, stitching and embroidery was significant for females at 33% while for males unskilled factory work stood at 27% followed by self employment at 18%. It needs to be highlighted that skilled labor only contributed to 18% of male and 9% of female employment. Batool’s research seconded the impact of lack of skills on employment. Providing reasons for unemployment, she articulated that while women in rural areas specified non-availability of jobs (48.8%) and lack of qualified training (30.5%) for their lack of labor participation, the biggest reason in urban areas was a lack of desire and need (37%) followed by further studies (26%) and lack of qualified training (19%).

: Reasons for Female Umemployment: District of Khushab

Both studies thus recommended higher investments in human capital including general education, though more importantly skills provision through formal vocational training or informal apprenticeships was highlighted as a key but not a sufficient factor. Tying it with employment opportunities along with decent working conditions would complete the loop required for increased female labor market participation needed for a demographic lift off.

But Haque argued beyond delivery of employment skills stating puberty and later transition to adulthood as a crucial capacity building period for both livelihood as well as health life skills. Provision of technical skills for employment was vital to eliminate negative social behavior including the vast suicide bomber pool but as important was an awareness of health issues as only it could limit risky behavior in addition to increasing the current 1 year period between marriage and child birth.

Moving beyond analysis, Khan provided a working model for transforming youth from passive victims to a promising resource for the socio-economic development of a community. He called for a paradigm shift among supply side educationalists unaware of the term youth social entrepreneur lamenting that only 1 out of the 27 principals of technical institutes even knew of the term. Youth Engagement Services’ (YES) model instead matched the huge unmet community services needs with the untapped talent of disadvantaged youth of the same community. It built youth confidence and assisted them though seed financing and incubation services to set up community based micro social enterprises. Concentrating on disadvantaged female youth, YES worked both at an individual level though provision of specific skills as well as at a collective level through youth service networks. Sustainability of the model lay in its community self reliance methodology as youth of the same community earned revenue by delivering need based services, while scalability depended on an organized youth community reaching out to the youth of other communities to join the YES Network.

With a lack of skills and services provision among most communities, YES promises to provide a plausible model for the delivery of education, health, emergency relief and skills development in communities. Developing, initiating and scaling of such self reliant community development models hold the key to the future of this youthful nation.

Citations