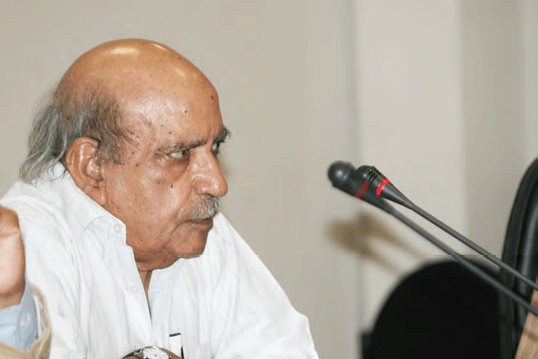

Mr. I. A. Rehman, former Chief Editor of The Pakistan Times and current Secretary General of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) was invited to deliver a talk on “Reflections: On the Changing Role and Dynamics of Media in Pakistan” on the 13th of October, 2010.

Rehman began his talk by providing a history of journalism in Pakistan. He stated that at the time of Pakistan’s creation, most literature was agitational, related to the politics of the period and raised issues that concerned the masses. At that time, English journalism comprising primarily of the two English newspapers Pakistan Times and Dawn had a narrow base and was patterned on British journalism. The problem of having two languages in national print media was thus inherited leading to the emergence of two categories of media. One media catered to the public mood and the other tried to impose a discipline derived from the British parliamentarians.

He stated with dismay that the State of Pakistan deviated from its democratic principles early on. By 1950’s, it had become difficult to sustain independent growth of journalism due to the interference of the Government. Gradually as differences emerged between East and West Pakistan, the Pakistani press could not develop into a National Press. Instead, it got divided into East and West Pakistan press compromising both a national purpose and journalistic values.

He emphasized that the period of the first military regime of Pakistan needed to be studied carefully to understand the changing role of media. The military regime of the

first martial law of 1958 practiced an extended exercise of establishing State hegemony over all institutions in the country. It began with controlling cinema- Censorship Act was rewritten and made stricter while State institutions of cinema were established. The attack on writers led to the establishment of a Writer’s Guild under State patronage to support the tradition of developing literary yes men and women. Other institutions followed including institutions of law and bar councils. Control over the press was also established through the creation of the National Press Trust, which bought newspapers and brought them under direct control. These actions resulted in State’s hegemonization of the spaces for expression, activity and creative growth.

He further stated that even the democratic governments followed the same anti-democratic and authoritarian systems. Elaborating, he argued that the media policy and institutions of Ayub Khan’s rule were maintained during Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s democratic government and no steps were taken to liberate the press. So the old system persisted even though the military regime was replaced by civilian rule. Ten years of controlled journalism had given rise to “handout journalism” whereby newspapers simply published an issued statement. Thus newspapers instead of becoming forums for debate became notice boards on which one stuck statements and press notes. To this day, when one opens a newspaper it is 70% statements.

“Control over the press was also established through the creation of the National Press Trust, which bought newspapers and brought them under direct control.”

Discussing recent history, Rehman suggested that after the end of the (Zia) military regime, Pakistani press needed 10-20 years to reestablish the principles and dynamics of independent journalism. But what happened instead was the overtaking of the press by electronic media. Today media is dominated by the electronic medium instead of print, and people form their opinions through what is shown on television and other electronic media. Thus they have a formed opinion even before the print media reaches them leading the print media to ape the electronic. Interestingly, this dilemma has been resolved by making the electronic media a monopoly of print media whereby all major electronic channels have their own newspapers. Overall, he argued that today’s media was either more commercial, business-oriented or power oriented. The newspapers now competed on the number of pages they printed and their aim had shifted from mass circulation through low prices to lower circulation at higher prices resulting in a greater reliance on television as advertisement rates on television were much higher than in newspapers.

“…the kind of critical function that the media should perform was re-ceding while its partisan role was increasing”

Rehman argued that ideally media should draw upon the intellectual and creative resources in society else it would have a very narrow base to work with. This explained the narrow base of Pakistani media as it had failed to draw upon literature, academics and intellectual pursuits. To make matters worse, all television channels had started copying one another without considering their individual requirements and creative input. For instance, if one channel started a talk show, everyone else would also start one without considering whether it suited the objective and purpose of the channel. Additionally, lack of proper training of anchors and reporters had also been detrimental to electronic media’s performance.

There had also been a steady decline in the quality of newspapers as number of commentators in a newspaper had become the benchmark of its success. Opinions were stated without factual basis or proper referencing. No newspaper except one in Pakistan had a reference library in comparison to 1963 during his service in a newspaper when all had reference libraries. The old school of thought in Pakistani media was that all news had to be factual and opinions were to be found only in opinion columns. Today’s newspapers however contained opinions in the news columns leading to biased and subjective reporting Another reason for the decline of quality of analyses in newspapers was that the reading public had gradually become less discerning and critical about content.

He recounted that the magazine was historically an important part of the newspaper in Pakistan as long articles discussing contemporary issues and providing food for thought, which could not have space in the newspaper became part of magazines. These commentaries, analyses and historical reviews were both edifying and illuminating. In comparing the two main categories of journalism in Pakistan, the English and Urdu journalism, he argued that the contemporary Urdu magazines still followed the old tradition and format, and were informative, edifying and educative. But the contents of English magazines had significantly changed mainly focusing on entertainment and fashion. For example, two major newspapers in Pakistan published magazines of about forty pages which only contained pictures of the elite class at various events and parties. This implied that there had been an emergence of a new upper middleclass, which attached very little value to serious journalism and was not concerned with acquiring historical, political or economic knowledge.

Based on the arguments presented earlier, he suggested that the kind of critical function that the media should perform was receding while its partisan role was increasing. Both electronic as well as print media had started engaging increasingly in criticism and faultfinding rather than a more solution oriented focus to enable people to bring about change. This excessive criticism was instead spreading negativity, a sense of helplessness and a loss of self-confidence among the population. Partly disagreeing with the recent prevalent feeling of unparalleled freedom of press, he stated that there were still certain issues which the media could not discuss. Instead, the greater freedom granted to all institutions including media was mainly due to the government’s dysfunctionality and its inability to control or supervise any institution.

Rehman concluded by emphasizing the significance of public discourse and the role of media. He explained that the progress of a nation depended not only on the strength of institutions but also on the strength of public discourse. It was the quality of discourse in a society that determined its ability to move forward. The quality of journalism and media was determined by the interplay between society and the institution as ideas ultimately come from the people. Even with a vibrant press, Pakistan still lacked behind because the recent public discourse in Pakistan was peripheral and superfluous rather than substantive and valuable. Thus it was important to strengthen the linkages between society and media, and it was the responsibility of conscious citizens to ensure that media as an institution was monitored and corrected.

“…media should draw upon the intellectual and creative resources in society else it would have a very narrow base to work with.”

The talk was followed by a Q&A session. Responding to a question about the role of PEMRA, Rehman explained that PEMRA had been designed in accordance with colonial laws meant to gauge and control freedom of expression. It violated the spirit of our age which demanded that these institutions were regulated by public representatives. The civil society had a very limited role in PEMRA as most of the decision making space was occupied by government representatives and functionaries.

Answering another question regarding the role of State media channel, the possibility of publicly funded media channels and the problem of compromised public benefit for corporate interest, Rehman provided a historical perspective that the State channel had been created in 1964 to enable Ayub Khan to win elections to be held in 1965 More recently the channel’s dynamics had changed due to competition from private channels, the money making motive as it also sold time to private channels, and some programming on matters of public concern. He argued that new forms of communication would ensure that State media would gradually lose its influence, but there was a possibility for public interest channels as over the last few years, few FM radio channels had made considerable progress and acquired a certain degree of respect in this regard. However newspapers and television channels had become lucrative businesses and now required much more investment than before. Additionally, the State had not done anything to reduce these costs but on the contrary had made access to information through newspaper and television more expensive for the public.

Regarding a question if media was promoting brutality, he agreed that there had been a decline in discipline in the area and the media needed to exercise greater caution. He said that in the colonial period censor code, showing third degree on screen was banned and wounds which were vulgar and repelling could not be showed.

Answering a last question on the role of corporate interest in media, he stated that media was amenable to corporate advise only to an extent. Although concessions to corporate interests were visible, still corporate sector did not have decisive influence. The oriental habit of looking to power and authority was more decisive and the assessment of where the locus of power was, guided and determined media policy.

“…progress of a nation depended not only on the strength of insti-tutions but also on the strength of public discourse.”

Citations