By Talal Raza

MPhil National Defense University 2017

Introduction:

The 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center transformed the world in many ways – one of them being that states began to opt for a series of legal and executive measures as part of the global “War on Terror”. Some of these measures included collecting a huge amount of personal data and information to ensure that states would be in a better position to preempt any new terrorist attempt. Pakistan was no exception to this changing security environment. It supported the NATO alliance in counter terror operations against Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. Later it also began to crackdown on home-grown terrorist groups through a series of executive and legal measures to fight terrorism. For instance, it launched a number of military operations in Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and destroyed terrorist training camps and hideouts; hunted down terrorists in urban areas through intelligence-based operations; seized hate material; and banned firebrand clerics from promoting sectarianism. The legal measures taken in this regard include (but are not limited to) amending the Anti-Terror Act (ATA) 1997, passing a new National Internal Security Policy (NISP) 2014, and giving sweeping powers to the military under the Protection of Pakistan Act (POPA) 2014. The rise of internet penetration also meant changing dynamics of terrorism. Although there have not been any major cyber terror attacks in Pakistan till date, terrorist presence on the internet was too significant to ignore; the cyberspace continues to provide an avenue for disseminating propaganda and to reach out to potential recruits by both the named and unnamed terrorist outfits. Thus the Pakistani government extended counter-terrorism efforts into digital space. It first promulgated the Electronic Transaction Ordinance 2002 and later, the Prevention of Electronic Crime Ordinance 2007 which criminalized damage to information systems and cyber terrorism.26 Further, the Pakistan People’s Party government enacted the Fair Trial Act 2013 the purpose of which was to be able to acquire warrants for digital surveillance of terrorism suspects.27 However, it was only after the Army Public School (APS) Peshawar attack which shook the nation, that a robust counter-terror strategy under the National Action Plan (NAP) was devised. Some of the measures included removal of moratorium on the death penalty, establishment of military courts and revival of the National Counter Terrorism Authority (NACTA).28 With respect to cyberspace, a subcommittee on internet/social media chaired by the Interior Minister was established29; articles specifically dealing with hate speech in online spaces and cyber terrorism were introduced within the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (PECA); and, Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) blocked 5078 anti-state and 1894 hate speech-related web pages/links to date.30 Further, the government has either acquired or are in the process of acquiring software that will allow increased digital surveillance.31 However, according to an investigation conducted by The Dawn newspaper in 2017, 43 out of 64 proscribed organizations still had a presence on Facebook.32 There have also been reports that banned organizations had taken to social media to make appeals for animal hides’ collection during Eid-ul-Azha.33 This was in the midst of a government ban on proscribed organizations from collecting hides since their sale was an important source of funding for them. Although the government has tried to take down websites and Facebook pages of banned organizations, these re-emerge and continue to operate with impunity, thereby disseminating “hate material” and propaganda. In 2013, the government took down Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan’s (TTP) social media page “Umar Media’’. However, it re-emerged within a few days. As of today, this page still exists. In fact, TTP also continues to post its press release over a WordPress blog. Similarly, many social media accounts and web pages attributed to groups such as Baloch Republican Army, Hizb ut Tahrir et al., continue to be present. The Pakistani cyber security regime is quite weak when it comes to dealing with such emerging threats. According to the United Nations Agency on Information and Communication Technologies called International Telecommunication Union (ITU), Pakistan ranks even below Afghanistan when it comes to having robust cyber security readiness.34 Furthermore, officials have acknowledged that there is no clearpolicy to battle terrorism in cyberspace.35 That said, lumping together of cybercrimes with terrorism in PECA, coupled with lack of transparency in digital surveillance of terror suspects, gives the state a carte blanch to obfuscate political and progressive voices in cyberspace.36 Such measures have drawn criticism from rights activists on the grounds that they infringe upon digital rights (civil liberties in cyberspace) and violate constitutional as well as international rights of Pakistani citizens. Unfortunately, the successive governments’ reluctance to take on board rights groups begs the question whether rights activists and government can ever reach a consensus. This paper tries to understand the gap between the government and rights groups by exploring: what constitutes terrorism in cyberspace according to Pakistani legal regimes; what legal and executive measures have been taken to curb it and do these measures infringe upon the digital rights of Pakistani citizens? In light of the findings, it tries to answer how digital rights of Pakistani citizens can be preserved while curbing the menace of terrorism in cyberspace. To explore the above questions, multiple sources have been used including newspaper articles, books, research papers, and Government and NGO reports. Sixteen in depth interviews were conducted including six government officials from the Ministry of IT, Ministry of Interior, Pakistan Telecommunication Authority, Federal Investigative Agency and Punjab Information Technology Board; six rights activists from renowned NGOs including Bytes for All Pakistan and Digital Rights Foundation. Further two lawyers with ICT expertise, a security expert and a journalist were also interviewed.

Conceptual Framework:

Discussions at a global level with respect to the citizen’s digital rights have broadly drawn a consensus on universal right to: have access to the internet; exercise the freedoms of association, assembly and expression in cyberspace; and privacy. These rights have been recognized by multiple resolutions passed in the United Nations Human Rights Council.37 Further, efforts are also being made to re-interpret the traditional human rights frameworks, covenants et al. that have long been universally recognized.38 All discussions pertaining to digital and human rights should be linked with the human security framework as it gives room to go beyond the silos of the physical and digital realm and form a more holistic outlook. In short, the question of digital rights should be understood within the context of physical wellbeing of citizens.The concept of human security as proposed by the United Nations in 1992 emphasizes measures to enhance the overall wellbeing of the inhabitants of a state in addition to safeguarding its borders. It comprises seven elements including economic, food, health, and environmental, personal, community and political security. Even though the Human Security model was proposed at a time when threats emanating out of cyberspace had not been envisioned by the proponents, these elements of the human security framework can be extended to cyberspace as well. For instance, the right to freedom of expression and freedom of association and assembly, which are a part of political security, apply as much to cyberspace as to physical space. Similarly, theft of USB containing sensitive information not only poses a threat to one’s privacy and personal security but can potentially affect health security. Hate speech perpetuated by sectarian groups on social media can pose a threat to a person or community’s security. It can therefore be argued that a state’s counter cyber terror and cybercrime methodology should be assessed in light of digital rights and human security frameworks as some of these interventions may have adverse implications for the human security of the population.

Pakistan’s Terrorism Framework in Cyberspace

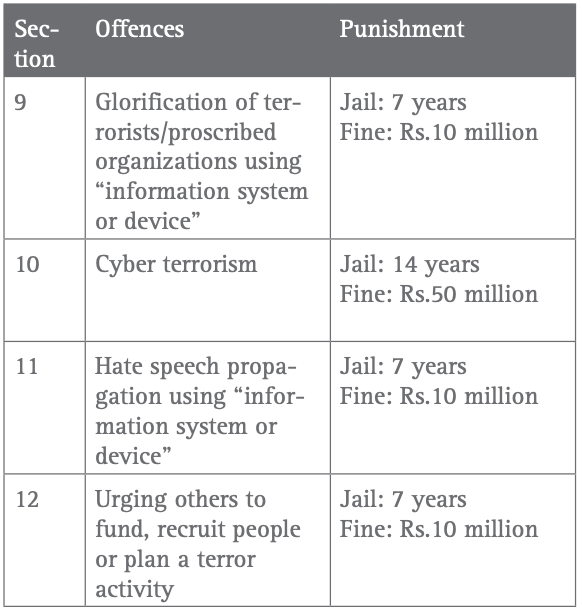

Definition: This study has analyzed the 1997 AntiTerrorism Act, and the 2016 Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act to identify the contours of terrorism in cyberspace. Although these laws do not explicitly define terrorism in cyberspace, they have incorporated punishments to deal with acts of terror online. Accordingly, the actions that could fall within the ambit of terror in cyberspace include all actions that: instill fear in government, public or any community or group; damage critical infrastructure (e.g. NADRA database);glorify any terrorist or proscribed organization or their activities using an information system or electronic device; spread hatred against a sect, ethnicity or religion using any software, system or electronic device;and motivate other people through any software, system or electronic device to fund, join or plan terrorist activities.

Legal Framework: There are a number of existing laws that can potentially deal with the issue of terrorism over the internet. For instance, the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), 1860. Although the PPC does not explicitly spell out provisions against terrorism over the internet, it’s hate speech clauses have been invoked to register cases against people for propagating hate speech online.39 The language of Anti-Terrorism Act, 1997 (ATA) is broad enough to be used in instances of hate speech over the internet and has been evoked on multiple occasions.40 The Fair Trial Act, 2013 (FTA) allows the government to carry out electronic surveillance (including email, Internet) of people suspected of terrorism related activity. According to FTA, if an officer of a law enforcement agency is suspicious that anyone might be committing acts of terror, he/she can file an application with his departmental head along with all relevant documents and proofs. The departmental head will review the application and send it to the Minister of Interior. The Minister of Interior will approve the application after reviewing it. There is hardly any chance of rejection if the application is coming from the powerful intelligence agencies. After its approval, the officer will submit the application to the High Court judge in secret chambers, who may issue the warrant after ascertaining the case on its merit. Even though the warrant is issued for a duration of sixty days, there is no bar as to the number of times a warrant can be issued against the same application.41 There is no existing record of how many warrants have been issued under the FTA thus far. Further, it has been established from different sources that government institutions have the capacity to carry out widespread surveillance which can allow them to track emails, Whatsapp, Viber call data et al.42 The Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) 2016 is the only law that explicitly recognizes the threat of terrorism over the internet and provides for the following punishments.

Since PECA has been enacted only recently, only one case [of cyber terror] has been registered under this law thus far. This case pertains to the suicide of a Sindh University student in which her friend was alleged to have misused her personal information, making her take her own life.

44 Institutional Framework: A number of executive measures have been undertaken by the Government of Pakistan against terrorism in cyberspace. Under PECA, the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) would primarily be looking at terrorism over the internet. However, other agencies such as Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) may also be involved. A report pointed out that the ISI had requested the Ministry of Interior to give it a stake in battling cybercrimes detrimental to national security.45 The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) has been given the content management role under PECA, and though information is not available, PTA claims to have taken down terrorist content. Similarly, Punjab Information Technology Board (PITB) has made some technology interventions. They recently handed over Hotel Eye software to hotels and asked them to enter the details of their clients. This software is linked to a central command system of the police and flags any name with criminal history. Further, the PITB’s initiative “Peaceful Pakistan’’ is an attempt to promote a peaceful and positive image of Pakistan online while also receiving complaints against hate speech which are forwarded to the PTA.46 Lastly, NACTA has also been taking part in building counter narratives in cyberspace through informal measures despite being under-resourced.47

Digital Rights Concerns:

Multiple interviewees raised the issue that laws dealing with terrorism were overbroad. For instance, according to the framework’s prescribed definition of terrorism, the lowest threshold for anyone to be declared a terrorist is that their actions infuse fear among the public or government or a section of society, irrespective of whether the act has religious or political undertones. By this yard stick, if one walks in and starts shooting, even if it is not politically motivated, it would still fall under terrorism as it infuses fear among the public. This results in overburdening the anti-terrorism court with cases that are essentially without a political motive. Moreover, there are different types of punishments for the same crime, that is, for hate speech under ATA, PECA and PPC. This leaves room for the authorities to pick and choose when to use the law that awards less punishment or one that awards maximum punishment, thus providing room for both misuse as well as disproportionate use of power. For instance under ATA, a man was sentenced to thirteen years imprisonment for posting religiously offensive material on Facebook when according to his defence lawyer, he had only “liked” the post.48 Selective accountability has been another growing concern. For instance, the government is very reactive towards political dissent as is evident from the recent crackdown against social media activists. However, it has failed to take down pages of proscribed organizations that use the internet to recruit, receive funds and plan terror activities. Whatever measures have been laid down, there seems a general lack of interest on the part of state institutions to share how they are using certain powers to battle terror in cyberspace. For instance, PTA claims to have taken down many terror websites but has never shared the list of these blocked websites. Also under FTA, the government can acquire warrants, the life of each warrant being 60 days. While FTA puts a bar on the life of a warrant, it doesn’t put a limit on the number of warrants that an officer can receive for the same case. From a digital rights perspective, some suggest that the government should also specify what sort of surveillance equipment they are using, as one surveillance technology may be more intrusive than another, and may impinge upon the privacy of citizens. Further, a disproportionate use of surveillance technology may end up revealing more information about people than is required. A concerning research finding was that in spite of an extensive framework for tackling terrorism in cyberspace, extra judicial measures have been used to silence political dissent. For example, in January 2017, four bloggers were picked up mysteriously. While they were missing, an organized campaign commenced against them, declaring them blasphemers over social media.49 After three weeks, they reappeared but quickly left the country as asylum seekers. No case was registered against them and the FIA stated in the Islamabad High Court in December 2017 that they had not committed any blasphemy. Interviewees who have closely followed the case shared that these bloggers did not have a favorable opinion of security policies being pursued inside Pakistan and that is the reason why they were picked up.

Conclusion & Recommendations

Based upon the above discussion, it is clear that the contours of terrorism in cyberspace as defined by law in Pakistan are broad. Application of such laws can actually harm rather than help the fight against terrorism because of: a loss of focus; data aggregation of various types of cases leaves the data useless for analysis; overburdening the anti-terrorism courts; and increasing the possibility for the misuse of power, thus discrediting the anti-terror regime. Further, the application of laws related to cyberterrorism will become even more critical as internet access increases in the country. It is also quite evident from the examples discussed above that counter terror measures not only have the potential to violate the digital rights of citizens but in some cases, these measures have been used disproportionately to try persons who were not affiliated with any proscribed organization. Ironically, some proscribed organizations have enjoyed unbridled freedom to operate in cyberspace while others have been clamped down upon. The legal lacunae because of overbroad laws, selective accountability, lack of transparency, withholding of information, and extra-judicial measures taken by the state go against the digital rights of citizens and can only be addressed through a sustained dialogue among state institutions, government, parliamentarians and civil society. In light of this, following recommendations are proposed to balance digital rights against counter terror measures:

Remove Duplication & Make Laws More Specific: There is a need to review and revise laws related to terrorism to ensure a coherent definition, while removing any duplication by assessing to what extent punishment under various laws corresponds with a similar nature of crime. Efforts should be made to strike down outdated laws and replace them with revised anti-terror laws that are specific and provide uniformity. Further, overbroad clauses need to be made more specific. Otherwise, it would be difficult to prevent abuse of such laws.

Strengthen Oversight and Increase Transparency: An institutionalized mechanism should be put in place for both public representatives and civil society to conduct accountability of government’s measures against terrorism. For instance, the government should be open towards sharing with the public, the number and nature of terror related websites/social media accounts that have been taken down, and the number of warrants issued in a certain time period. They should also share the nature of surveillance being carried out so as to put to rest talks about the infringement of citizens’ digital rights.

Build Capacity of Law Enforcement Agencies & Judiciary on Digital Rights: To make cybercrime prevention more effective without impinging upon citizens’ digital rights, it is imperative to prevent disproportionate exercise of powers conferred upon different state agencies through legal measures. Thus, both law enforcement personnel as well as members of the judiciary need to be trained on counter terror legislation for cyberspace and digital rights framework. Currently, only Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Judicial Academy trains judges on cybercrimes.

Bibliography

Herald, “Surf safely: Evolution of Cyberspace Laws in Pakistan,” Herald.dawn.com, May 10, 2016, accessed January 10, 2017, http:// herald.dawn.com/news/1153380. Waqas Mir, Digital Surveillance Laws in Pakistan: A White Paper by Digital Rights Foundation (Lahore: Digital Rights Foundation, 2014). Irfan Haider, “Terrorists operating 3000 Websites to propagate Agenda in Pakistan,” Dawn.com, August 14, 2015, accessed August 14, 2016, http://www.dawn.com/news/1200276. Azam Khan and Aamir Saeed, “Fighting Terror: Institutional Structur in the Context of NAP,” Conflict and Peace Studies 7, no.2 (Spring 2015): 29-38. Ramsha Jahangir, “Pakistan’s online clampdown,” Dawn.com, October 28, 2018, accessed January 27, 2019, https://www.dawn.com/ news/1441927/pakistans-online-clampdown.Jahanzaib Haque & Omer Bashir, “Banned outfits in Pakistan operate openly on Facebook”, Dawn.com, May 30, 2017, https://www.dawn. com/news/1335561/banned-outfits-in-pakistan-operate-openly-onfacebook. Jawad Awan, “Banned Organizations to go Online to Collect Hides,” The Nation, September 21, 2015, http://nation.com.pk/editorspicks/21-Sep-2015/banned-organisations-go-online-to-collecthides. Talal Raza, “Use of Facebook by Ethnonationalist Groups from Pakistan,” The May 18 Memorial Foundation. Accessed July 15, 2016, http://www.518.org Jahanzaib Haque, Pakistan’s Internet Landscape 2016: A Report by Bytes for All, Pakistan (Islamabad: Bytes for All, Pakistan, 2016). Shahid, Kunwar. “Cybersecurity Work in Progress…: An Analysis of Pakistan’s Cybersecurity Dilemma.” MIT Technology Review Pakistan 2, no.2 (April 2016): 26-31 ; Verda Munir. “The Debate on Cybercrimes Law: A Study of the Proposed Law and the Way Forward.” MIT Technology Review Pakistan 2, no.2 (2016): 32-37. James Vincent, “UN condemns internet access disruption as a human rights violation,” The Verge, July 04, 2016,accessed January 27,2019,https://www.theverge.com/2016/7/4/12092740/un-resolution-condemns-disrupting-internet-access; Article 19, “UN HRC maintains consensus on Internet resolution,” July 09, 2018, accessed January 27, 2019, https://www.article19.org/resources/un-hrc-maintains-consensus-on-internet-resolution. Global Network Initiative, “Principles,” accessed December 25, 2016, https://globalnetworkinitiative.org/principles/index.php ; Kimberly Carlson, “Necessary and Proportionate: International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance,” accessed January 19, 2017:1-15,https://necessaryandproportionate.org/july-2013-version-international-principles-applicationhuman-rights-communications-surveillance. Ministry of Interior Government of Pakistan, Annex Z: Historical Overview: Counter Terrorism Laws in Pakistan (Islamabad: Ministry of Interior Government of Pakistan, 2014).

Citations